China’s tennis plan changes the game. Why the global sports world should care

Instead of another policy memo, Beijing has unveiled a blueprint that blends politics, sport and economics. Racket One obtained the full text and pulled out the key insights for the global tennis industry.

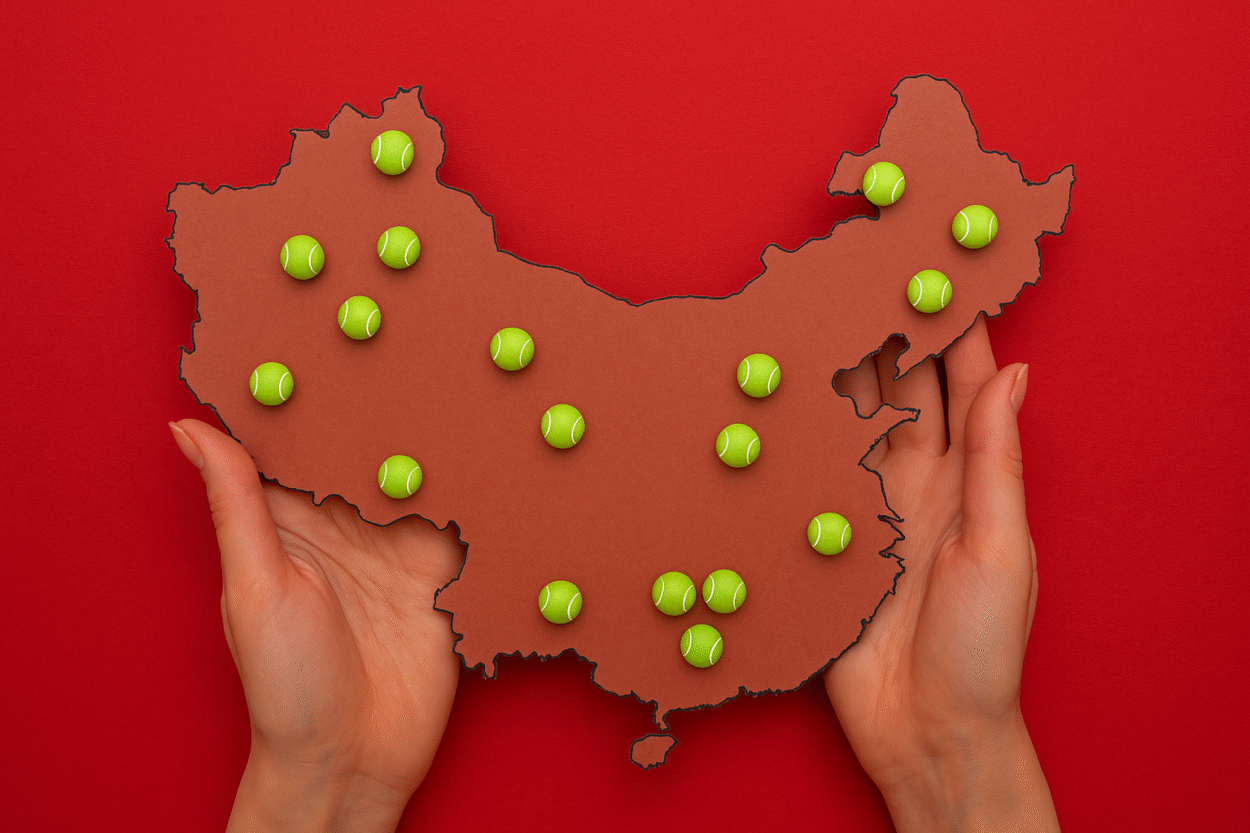

China’s new tennis plan is not just another directive from the state. It is a 41-point reform program designed to reshape the sport from grassroots participation to the Grand Slams. Unlike earlier fragmented initiatives, this plan combines elite performance, mass engagement and economic strategy under one umbrella.

For federations in the US, Britain and Europe, this matters for two reasons. First, it shows how central planning can accelerate participation at a speed Western systems rarely achieve. Second, China is using tennis as a tool of influence – from new tournaments to player development models – and that could reshape calendars, sponsorship flows and the junior ecosystem worldwide.

Development targets of the plan

The plan sets ambitious numbers: at least 10 Chinese players inside the world’s top-100, over 100 professionals and coaches competing internationally, 10 strong tennis provinces, 100 tennis-focused cities, and tens of thousands of youth clubs nationwide.

(The document does not specify deadlines. Given its place within China’s five-year planning cycle, these goals should be read as mid- to long-term ambitions, likely stretching toward 2030, – note from Racket One).

The vision is bold, but the round numbers look more like slogans than forecasts. Producing even one top-50 singles player is a long process. Expecting ten at once feels more like wishful thinking. Still, the grassroots system being built is impressive and worth watching.

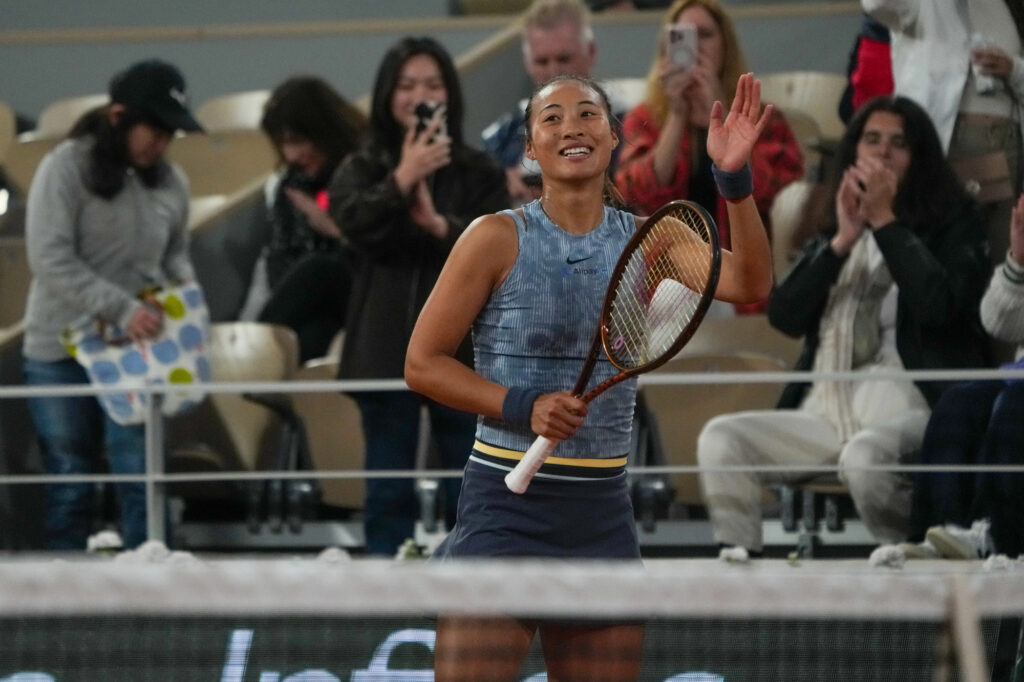

Right now, women’s tennis is clearly ahead: several Chinese players are in the WTA top 100, led by Qinwen Zheng, who is currently ranked No. 7. On the men’s side, though, the gap is stark — Bu Yunchaokete is the only Chinese player in the ATP top 100, sitting around No. 70. This contrast highlights both the progress already made and how far China must still go to meet its 2030 goals.

Creating a unified China Season

Instead of scattered international events, Beijing wants a single brand for all professional tournaments held in the country – the China Season. The goal is to raise their commercial value and visibility in the ATP and WTA calendars, essentially an Asian answer to Europe’s clay swing.

The branding idea is sound. Sponsors and fans respond to a clear identity. But tennis calendars are already packed, and finding room for a “China swing” may be harder than drafting it into a government plan.

Grassroots expansion: tennis in schools and malls

The Small Tennis Project aims to put the sport everywhere – in schools, shopping malls, residential neighborhoods and even tourist resorts. It is a classic top-down approach: saturating daily life with opportunities to play.

This may be the most innovative part of the plan. Western federations often dream of “making tennis a lifestyle,” but China is the only country willing to legislate it. With centralized authority, rollout can be rapid.

The real question is quality and sustainability. Once political attention shifts, will participation remain? State-driven enthusiasm often burns bright but fades quickly.

A homegrown junior Grand Slam

The blueprint also calls for staging four major national youth tournaments – essentially a junior Grand Slam on home soil. For young players this lowers costs and creates more opportunities without international travel. For the global system it is a statement: China wants its own development ladder alongside ITF pathways.

It is a logical move, but there are risks. If juniors compete only domestically, they may stall when facing international opponents. Still, for parents and sponsors the promise of a “Chinese Slam” is a powerful selling point.

Tennis as an economic driver

Beyond competition, the plan ties tennis directly to tourism, merchandising and urban branding. It mentions themed hotels, creative products and city campaigns. Few countries would include this in a state sports plan, and that novelty is striking.

This is where skepticism meets opportunity. On paper, tennis resorts sound like a marketing fantasy. In practice, China has the scale to try it.

Western federations may not copy the model, but they can study how tightly sport, tourism and retail can be linked.

Why China’s tennis blueprint matters

The plan mixes ambition, ideology and industrial policy. Some goals look like slogans rather than strategy, but the scope is unprecedented. For the global tennis community, the lesson is not to copy the numbers but to watch how China experiments with scale, branding and integration. Whether it produces a wave of champions is uncertain. What seems more likely is a continued shift of the industry’s center of gravity toward Asia.

Cover photo: Depositphotos. Custom edit by Racket One